George Blake – perhaps the most notorious double agent – has died, but his treachery was not the only scandal to befall Britain’s Secret Service in the 20th century.

Blake’s double-crossing is often mentioned alongside the notorious Cambridge spy ring – another group of establishment Britons who leaked countless secrets to the Soviets.

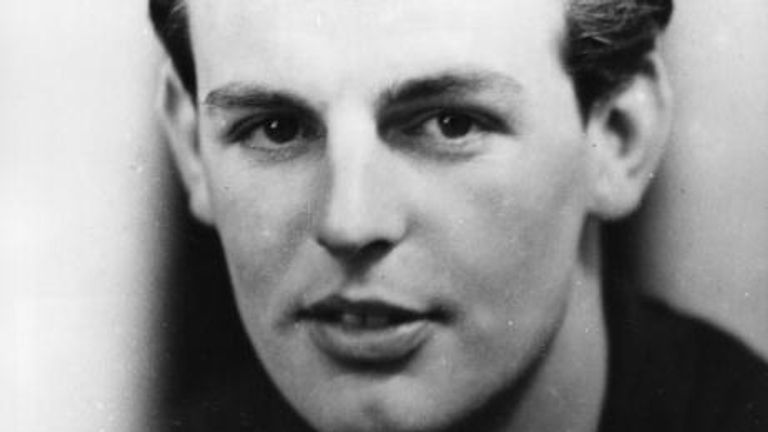

It was made up of men who studied at the city’s famous university in the 1930s: Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, John Cairncross and Harold “Kim” Philby.

Blunt, who was teaching at the university, helped recruit most of the group.

They carried their communist beliefs with them into jobs in government and the intelligence agencies; with Philby working as a journalist and then MI6, Blunt working for MI5 and Maclean and Burgess becoming diplomats.

But for years, from before the outbreak of the Second World War to the early days of the Cold War, they were passing information to the communist Soviet Union.

They all had handlers in London and were said to have been referred to as the “magnificent five” by Soviet intelligence.

Burgess alone handed 389 secret files to the KGB in the first half of 1945, according to documents from KGB defector Vasili Mitrokhin released in 2014.

However, it is Philby who’s believed to have done the most damage while leaking information from his senior position in MI6.

At the end of the war he was made head of the anti-Soviet section, meaning that, ironically, the man tasked with fighting the Soviet threat was actually working for the enemy.

He later became the chief British intelligence officer in the US, working in the Washington embassy.

Suspicions started to fall on the members of the Cambridge ring after the war.

When Philby learned there were suspicions about a mole passing secrets to the Soviets and that Maclean was a suspect, he told Burgess to tip off Maclean in London.

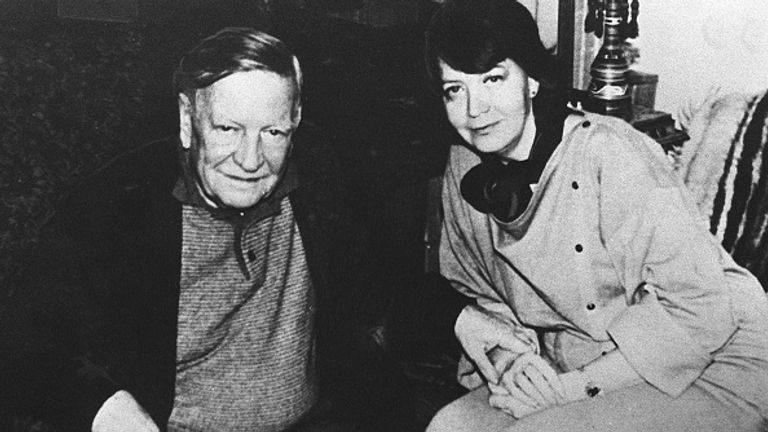

The pair made headlines when they fled Britain to France in 1951, but it wasn’t until 1956 that it was confirmed they had defected to the Soviet Union.

Files from defector Vasili Mitrokhin suggested the two men were actually regarded as something of a liability by the Soviets.

One document describes Burgess as “constantly under the influence of alcohol” and in danger of disclosing his double-agent status, with Maclean also described as a drunk and “not very good at keeping secrets”.

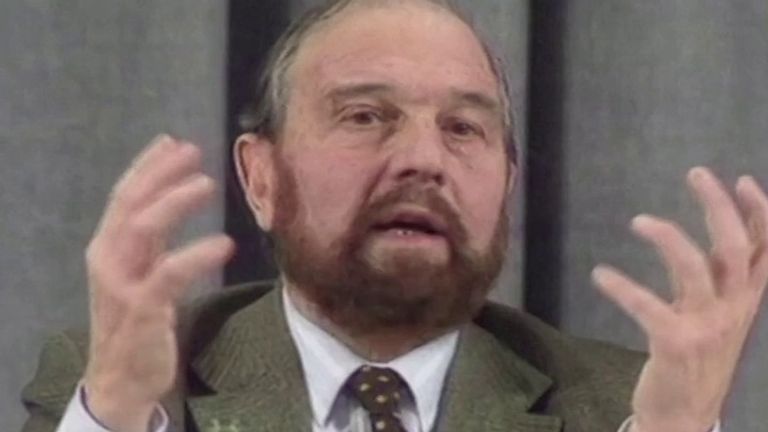

Philby resigned from MI6 when he came under suspicion himself as the “third man” – although there was not enough evidence to prosecute him – and became a journalist in the Middle East.

The net started to draw in though during his time in Lebanon, and he disappeared in January 1963, fleeing to the Soviet Union where he was given asylum.

He went on to work with the KGB, training spies for missions in the West, and was given a funeral with full state honours when he died in 1988.

In 1990, he appeared on a Soviet postage stamp, such was the regard he was held in.

The full impact of the damage done by the Cambridge Ring is hard to quantify.

But the fact that one of MI6’s top officers and other elite establishment figures were Russian spies was a huge embarrassment and damaged US trust in British intelligence for years.

In exile in Russia, fellow double agent George Blake later recalled how he got gotten know Maclean and Philby – and reminisced years later about drinking martinis with the latter.

Maclean died in Russia in the 1980s, Burgess in 1963, and Blunt died in London in 1983.

John Cairncross, the last to be publicly identified, died in 1995.