Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey has urged the EU not to pick a fight over post-Brexit access for financial services and accused it of demanding tougher standards of the UK than other countries.

Brussels has been slow to grant “equivalence” status allowing UK firms access to the bloc in the way that has already been granted to Canada, the US, Australia, Hong Kong and Brazil.

That was despite the UK starting off from a position of following the same rules as the EU, unlike those countries, Mr Bailey pointed out.

He said that the EU’s position was that it wanted to “better understand how the UK intends to amend or alter the rules going forwards”.

But Mr Bailey said: “This is a standard that the EU holds no other country to and would, I suspect, not agree to be held to itself.”

The governor said it appeared to mean Brussels was either taking the “unrealistic, dangerous and inconsistent” view that rules should not be changed in the future or that if they do, the UK should not do so independently of the EU.

That would be “rule-taking pure and simple” and “not acceptable”, Mr Bailey said in a speech to financial executives.

He said that did not mean the UK was out to create a “low regulation, high risk, anything goes financial centre and system”.

However, he argued “as the world moves on, so the rules need to adapt”.

Britain is already looking at easing “heavy duty” international banking rules for small banks, in a similar way that the US and Switzerland do, Mr Bailey said.

But it is also trying to opt out of EU plans to water down the way lenders can measure the level of capital they hold in case of stress.

Rules for the insurance sector are also being reviewed.

Mr Bailey said the UK had “a very bright future competing in global financial markets underpinned by strong and effective common global and regulatory standards”.

He said the world had “the opportunity to move forward and rebuild our economies, post COVID, supported by our financial systems”, adding: “Now is not the time to have a regional argument.”

London, Europe’s pre-eminent financial centre, dominates trading in the multi-trillion dollar currency markets but its firms no longer enjoy “passporting” access to the EU.

That has pushed a number of firms to shift assets away from the City and set up or expand operations in other hubs such as Dublin, Frankfurt and Paris.

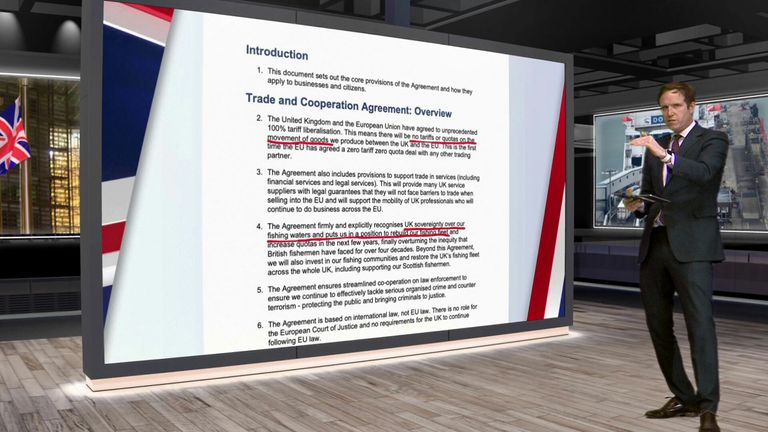

Britain’s new trade deal with the bloc, which took effect on 1 January, does not cover financial services and the City looks set to be given only “equivalence” based access for the future.

PwC has estimated that Britain’s tax receipts from the financial services sector – currently accounting for more than 10% of the total – are set to start falling this year as a result of Brexit and the impact of the pandemic.