To the west of New Orleans on the banks of the Mississippi a few grand old plantation mansions stand testament to a bygone age of slavery.

Now the riverine corridor has a new dubious distinction.

The sugar cane plantations have been replaced with industrial plants, huge petrochemical and industrial monsters, belching out pollution and clouds of gases.

And the descendant of the plantation’s slaves live in the poor, largely black communities wedged among them.

They have a name for this stretch of river.

Cancer Alley.

The area grabbed national attention when incoming US President Joe Biden singled it out by name in a speech, pledging to tackle the “disproportionate health and environmental and economic impacts on communities of colour” there.

More recently UN human rights experts condemned what they called the environmental racism in Cancer Alley, saying the “African American descendants of the enslaved people who once worked the land are today the primary victims of deadly environmental pollution”.

For the people who live there, it is long overdue but welcome recognition of the reality they say they have known and suffered for generations.

They hope it will win them support in their current struggle against plans for a huge new plant that would dwarf its neighbours, creating one of the biggest plastics plants in the world.

‘I felt like we are nothing’

Sharon Lavigne remembers the day she heard about the plans. She was in her high school classroom teaching when her daughter passed on the news.

“I felt despair, felt right. I felt like we are nothing.”

Sharon lives two miles from the site of the plant owned by Taiwanese company Formosa Plastics. Her neighbours were told it was a “done deal” they could do nothing to stop.

“Month after month, I went home with despair, hurt.

“I was crying at night and I would pray: God, are we supposed to just pack up and leave? What are we supposed to do?”

But Sharon resolved to fight the plans, calling meetings of neighbours which grew quickly in number.

Her group has teamed up with others and won support from national campaign organisations.

Together they’ve won court victories slowing the plant’s approval process.

She is determined to see it off completely.

“I’m going to fight to the end. Yes, indeed.

“That plant could be two miles from my house.

“They must be losing their mind.

“God put the right person here to fight God. But the fight is in me.

“This is my home. This is my people and I’m going to fight for me and my people.”

For its part Formosa Plastics told Sky News that the plans for the new plant meet “all regulatory criteria, using advanced emissions reduction mechanisms and extensive measures to protect the environment”.

Campaign groups say the plant would release tens of thousands of tons of known carcinogens into the atmosphere and huge amounts of carbon dioxide.

As we travelled Cancer Alley, everyone we spoke to in its small poor black neighbourhoods either had cancer or knew many others who do.

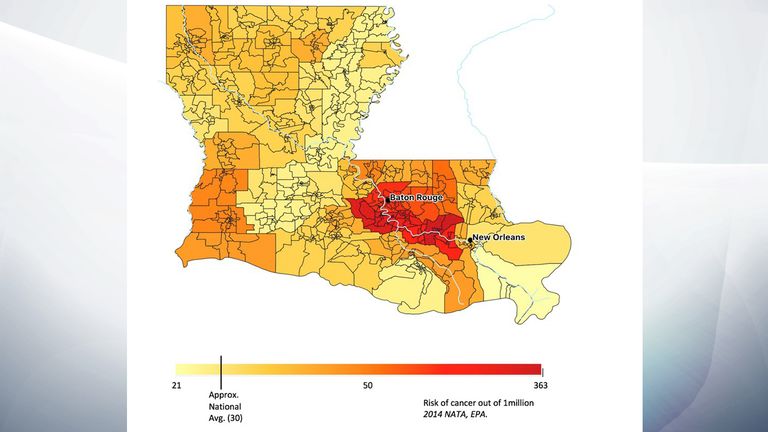

The State of Louisiana insists cancer rates aren’t unusually high here, but federal data from the Environmental Protection Agency suggests they are well above the national average.

Janice Ferchaud was typical of the people we met.

“It’s me, myself, my brother. My sister. I have about eight cousins and my neighbour. Oh. And it’s quite a bit more but at least for sure in this area where I’m at is 20 people have cancer.

“I’m just happy that the Lord took it away from my body.

“But I got a little cousin and she started in a project. This child is in her 30s and she had to have both her breasts removed, my sister had to have both of her breasts removed, and that chemo is just tearing them down.”

The State of Louisiana told Sky News: “Great care is taken in the site selection process to identify locations that safeguard communities and their residents.

“State and federal regulators require an extensive environmental permitting process before construction can begin.”

The process, it says, is subject to public consultation.

But that is not how the people who live there see it.

‘They’re the weakest people, they’re the poorest people’

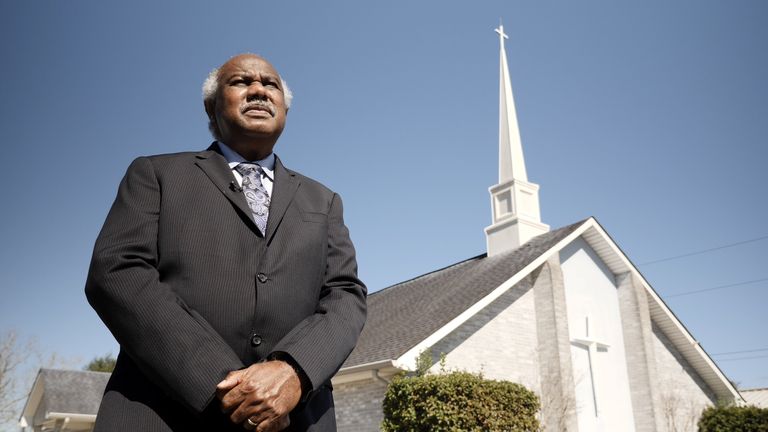

After Sunday service, Pastor Lionel Murphy shared his thoughts with us and agreed with the UN human rights experts’ claim that environmental racism is at play.

“They’re the weakest people, they’re the poorest people, and they’re often not the most educated people,” he said of the residents.

“So we put the plant there, you know, and the plantation mentality has been here.

“Many of these plants are located on old plantations. It goes back a long way, a long way, and it’s very disappointing but it’s time to turn it around.”

The people of Cancer Alley seem to have a champion in the White House who agrees on the need to turn the situation around.

They will try and hold him to it.