It was Franklin Roosevelt who first invited Americans to use “the first 100 days” as a measure of his success as president.

Nearly 90 years later, Joe Biden will mark his 100th day in the White House with the country – as it is on most things these days – divided over what he has achieved as president so far.

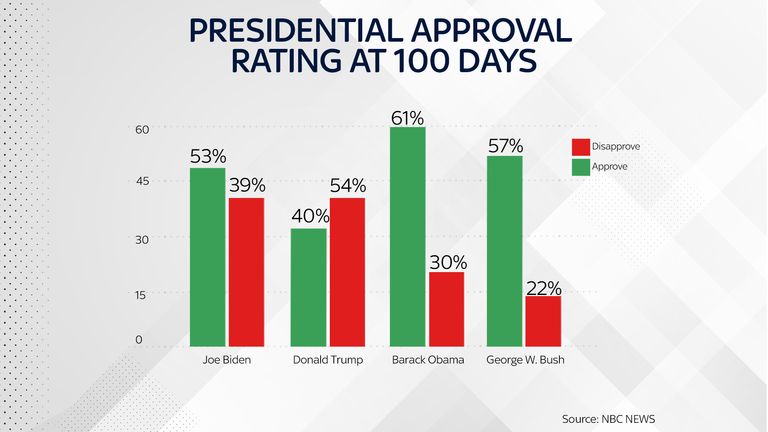

A raft of opinion polls to mark Mr Biden’s first 100 days shows the president’s approval rating – that measure beloved of American pollsters – ranging between 52% and 58%.

It is the third-lowest approval rating of any president in his first 100 days since the Second World War. The average for the last 14 presidents is 66%. The lowest ever? Donald Trump’s 42% in 2017.

That Mr Trump and Mr Biden have governed in such hyper-partisan political times certainly goes some way to explaining those historically low marks.

But, for the Biden administration, having the approval of a majority of Americans – however slim that majority – is a significant achievement.

There has been a palpable change in the feel of American politics: the daily reality show of the Trump era gone in favour of a sedate politics-as-usual under Mr Biden. The temperature and volume has been turned down.

But, on the campaign trail and the inauguration stage, Mr Biden promised a lot would happen in his first 100 days in the Oval Office.

For that reason alone, as arbitrary as the milestone remains, it is a good opportunity to measure what he and Vice President Kamala Harris have actually delivered.

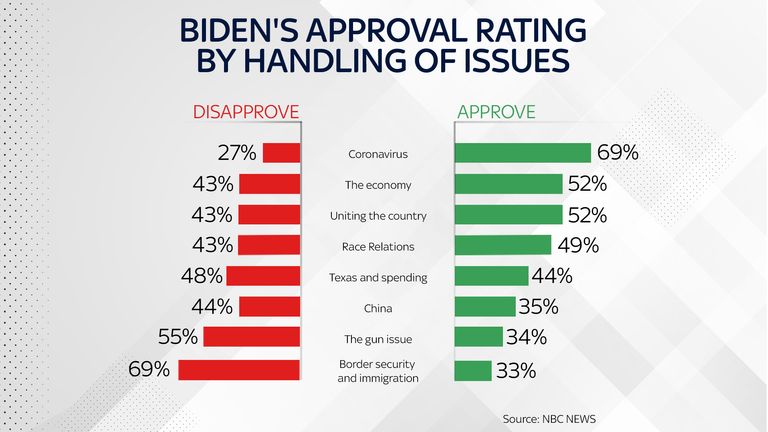

The 46th president scores highest in those polls on approval ratings for his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When Mr Biden promised to deliver 100 million vaccinations in the first 100 days of his presidency, critics said it was far too modest an ambition in light of the rapidly developing stocks of vaccine.

In fact, more than double that number of shots have been administered – with almost 100 million Americans now fully vaccinated.

The vaccine distribution plan released during the transition from the Trump administration to Biden’s appears to have been effective as does the new coronavirus taskforce and its regular public briefings.

The visibility and high profile of experts like Dr Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, as the faces of the fight against the virus is also in contrast to the approach of the prior administration. Mr Biden, unlike Mr Trump, rarely appears at taskforce briefings.

He has also, unlike Trump, never criticised or blamed the World Health Organisation for the spread of the pandemic. Instead there is a commitment to remain in the WHO and work on its reform.

Supporters of the former president will certainly point to the Biden administration inheriting the benefits of Operation Warp Speed, the Trump-backed race for a vaccine.

There are questions too on how the vaccination effort has reached poorer and minority communities. The Biden administration is also facing criticism for stockpiling vaccine at home when much of the rest of the world is in increasingly dire need.

The polls show another problem within US borders. Vaccine scepticism remains alarmingly high among some Americans. In a telling sign of the gulf between right and left in the country, 4% of Democrats say they will never receive the vaccine, among Republicans the figure is 24%.

Mr Biden’s biggest legislative achievement so far is one that was aimed at easing the economy hit from the pandemic.

The $1.9trn cost of the relief bill is staggering in scale and passed through Congress with Democrat votes alone. It sent money directly to Americans most in need and shored up things like unemployment benefits.

The sum of all of this, in the polls at least, is that Americans feel a bit more optimistic about the way out of the pandemic mire. A majority now say the worst is over in the US, in October a majority said the worst was still to come.

Americans – and their president – can look forward to a time when COVID-19 is not the dominant issue on the agenda.

Mr Trump used to measure the economic success or failure of his presidency by what was happening on Wall Street. If it is a reliable guide, then the Biden administration has made a healthy start with America’s financial well-being.

The markets are booming on the prospects of the country emerging from the pandemic’s grip and the forecasters’ hearty hopes about the chances of a speedy recovery.

The markets were less enamoured of Mr Biden’s plans to increase capital gains tax on the richest Americans to 43% from the current top rate of 23%. It was a taster of what is to come.

Biden wants to roll back the tax cuts that represented the signature legislative achievement of Mr Trump’s term in office. Passed into law along party lines in 2017, the tax cuts were meant to be “rocket fuel” for the economy.

In reality, non-partisan analysts said, most of the benefits were enjoyed by the richest in America and tax revenues actually slumped after the corporate tax rates was slashed.

Putting the top rate of tax back up to where it was will raise the money to pay the eye-watering bill for two of Mr Biden’s blockbuster legislative ambitions.

The combined cost of the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan will be somewhere in the region of $4trn. The pushback from political opponents has been intense but, as with the COVID relief bill, the Biden administration seems to be following the mantra of “go big or go home”. Which is fine if he can get them passed by Congress.

Unveiling the American Jobs Plan at a union training centre in Pittsburgh, Mr Biden described it as the biggest investment by jobs by the federal government since the Second World War, one that would reshape the US economy.

The twin-track of improving America’s creaking infrastructure and tackling climate change, he said, would create hundreds of thousands of jobs and make the country a global leader in green technology.

Similarly, the Families Plan would change the look of America. Billions would go into national pre-kindergarten and childcare, free community college tuition, paid family and medical leave and tax credits.

The plans are enormous in their scope and ambition and, even with Democrat majorities currently in both chambers in Congress, are far from guaranteed to become reality. On the left, they say the plans are too modest, on the right they say they cost too much.

Like raising the minimum wage and forgiving student loan debt, promises made on the campaign trail but yet to appear, what survives of Mr Biden’s big plans will be telling of his ability to actually deliver.

Since he began his run for the White House, Mr Biden has put the need to protect the environment at the heart of his plans for America.

His way of winning over more sceptical Americans is to dangle the prospect of millions of jobs he says will be waiting in the green energy future. The jobs and infrastructure plan he has proposed is heavy on the environmental imperative.

The virtual global climate summit that Mr Biden hosted was undoubtedly a campaign promise kept, but he has taken over a country that has plenty of work to do to persuade the world it can be a global leader on the issue.

Biden told the 40 leaders at the summit that the world is in a “decisive decade” and made new US pledges effectively doubling its commitment to cut carbon emissions.

But we all watched his predecessor remove the US from the Paris climate agreement and take domestic steps to promote fossil fuels. The world might wonder how much it can trust the longevity of any promises that come from this White House.

If actions speak louder than words, Mr Biden needs to deliver that green plan – spending billions on initiatives like making the country the world leader in electric vehicles, capping old oil and gas wells and switching away from the reliance on fossil fuels.

Americans certainly need no reminders of the impact of a warming planet as the millions in the path of intensifying wildfires and hurricanes, droughts and rising sea levels can tell you.

But the argument has not been won on Capitol Hill and it is part of the politics game in Washington to demonise in cartoonish terms policies to tackle climate change. Who can forget Donald Trump’s fact-free rants about the “tiny little windows” which he said would be imposed by one green proposal.

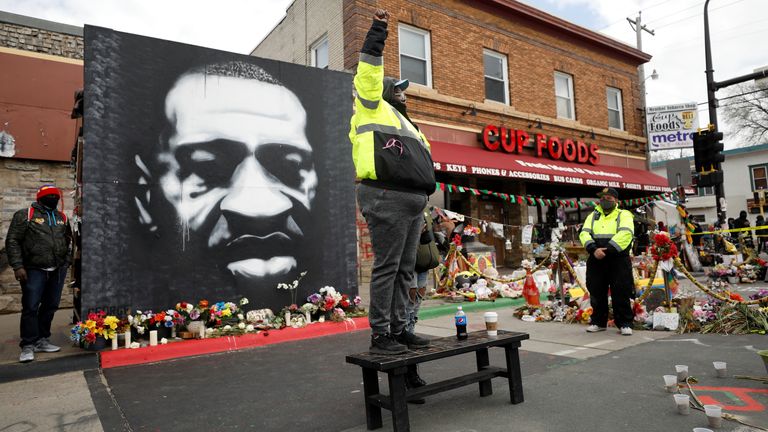

The conviction of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd once again put the need for a reckoning on racial inequality high on America’s agenda.

Joe Biden spoke to Mr Floyd’s family before he was president and again after the verdict in Minneapolis, promising that some good would come out of those awful events.

The federal civil rights investigation into the Minneapolis Police Department is the first action, maybe the first of many, to address public concerns.

But, as an example, the fate of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, introduced last year and still mired in the political machine in Congress, is illustrative of the challenges of actually getting anything done even with nationwide pressure.

A comprehensive voting rights bill pushed by Mr Biden is similarly stalled, so too a law targeting discriminatory sentencing and probation practices, plans for a police oversight commission have been dropped.

Every day that brings another harrowing video or more protests about police interactions with the black community ups the pressure on the White House to take concrete steps.

That, activists say, will be the moment that there really will be justice for George Floyd.

Mr Biden’s White House tried hard to avoid using the word “crisis” – but the situation at the southern border has undoubtedly been exactly that.

The polls show it is the issue on which he rates poorest with American people and there is a perception, fuelled by his political opponents, that he has opened the floodgates to a surge of migrants crossing from Mexico.

The administration has struggled to accommodate and process the tens of thousands of arrivals, many of them unaccompanied children, and the entreaties to would-be migrants that the border is still closed have failed to stem the flow.

For an administration that promised to right what it alleged were the wrongs of Trump’s immigration policies it has been an uncomfortable failure.

Mr Biden has handed the job of dealing with the crisis to Vice President Harris – and her work with governments in central America is likely to determine if the border can be brought under control.

The problems have eclipsed some of Mr Biden’s delivery of promises on immigration: a bill offering a pathway to citizenship to those in the US illegally, especially children, reuniting parents and children separated at the border, stopping construction of the wall and ending the ban on travel from majority Muslim countries.

Plenty more that was promised has yet to materialise and, as Donald Trump realised, there is major political capital to be made from the immigration debate.

Joe Biden’s first 100 days were always likely to be less headline-grabbing than those of his two immediate predecessors – the presidencies of Donald Trump and Barack Obama were history-making in their own, very different ways – but he knew enough about the White House before taking office to understand there are limitations.

On the international stage, Biden declared that “America is back” and scheduled the withdrawal of the remaining US troops in Afghanistan by this year’s 20th anniversary of 9/11. A multi-lateral American president should be a welcome sight for a world in turmoil.

He has made the right noises about bipartisanship at home, but faces a Republican Party wrestling with what its post-Trump future looks like, or even whether Mr Trump is actually still their future.

Those polls to mark 100 days show America just as divided as ever – 90% approval of Biden among Democrats, just 9% among Republicans – although one thing does seem to unite Americans – well, almost.

A CBS/YouGov poll found that 85% of Americans want the next four years to be “steady” or “normal”.