A small private hospital in India’s most populous state is being charged under the National Security Act for sounding the alarm over a lack of oxygen.

The director of the Sun Hospital in Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh told Sky News he faced being arrested at any time and his business seized after the police laid charges against him.

Akilesh Pandey, who owns and runs the hospital in the state’s capital, said four of his patients died on a single day when oxygen ran out.

He says he made repeated appeals to the state authorities warning them his supplies were running low but they failed to re-supply him with oxygen for 13 hours.

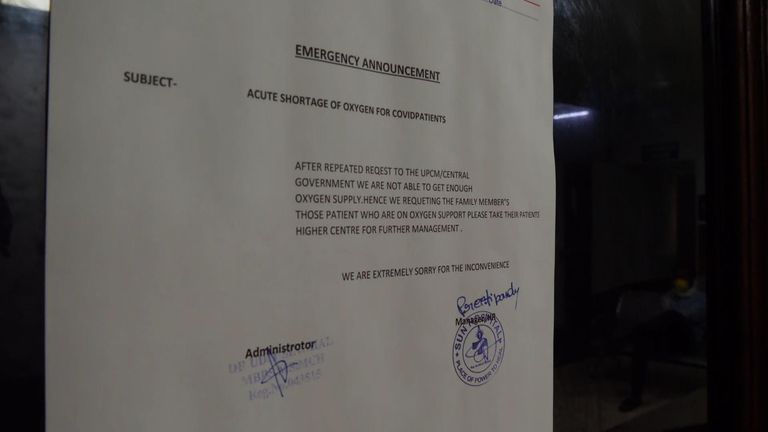

The notice he posted at the hospital on 3 May is still stuck up in places around the building.

It says: “After repeated request to the UPCM/Central Government we are not able to get enough oxygen supply, hence we requesting family members those patients who are on oxygen support please take their patients higher centre for further management.”

Days later, Mr Pandey says the police laid charges against him for “false scare-mongering”, raided his hospital and seized the CCTV from that day.

We arrived at the hospital as it was receiving a consignment of oxygen cylinders. The hospital’s oxygen-flow gauge showed once again it was running perilously low.

“I care about my patients enormously,” Mr Pandey told us. “They are my family but that day we could not give them oxygen.”

He showed us the oxygen supply just near the entrance of the hospital.

“These are the five oxygen cylinders that we had that afternoon…that would give one-and-a-half, to two hours of oxygen to patients.

“We decreased the pressure flow slightly so that we could extend the flow to about three to three-and-a-half hours hours….” he told us.

But the oxygen supply ran out by 9am the following morning – the relatives of those who died say that is what killed them.

One young man who lost both his 45-year-old aunt and 22-year-old cousin recounted how it was like “a never-ending nightmare”.

Eyewitness: India’s vaccine rollout stumbles before it starts

He said he hadn’t had time to process what’s going on: his uncle is still ill with coronavirus in the same hospital and he hasn’t had the courage to tell his aunt’s husband who is at home suffering with coronavirus too.

“My aunt needed high oxygen but when oxygen finished here, she was put on a concentrator but she could not manage by that.

“If there was oxygen she would not have died – my cousin would not have died.”

“This is the government’s responsibility to provide oxygen,” he said. “This has been made a COVID centre and the government must provide.

“The hospital is trying its best.”

The state’s High Court judges seem to agree, pronouncing last week: “The death of COVID patients just for non-supplying oxygen to the hospitals is a criminal act and not less than a genocide by those who have been entrusted the task to ensure continuous procurement and supply chain of the liquid medical oxygen.”

We have contacted the Uttar Pradesh authorities for a response but have yet to receive one.

The police charge against the hospital’s administrators is the latest in a line of draconian measures in Uttar Pradesh which has seen individuals arrested for putting out SOS appeals for oxygen.

The state’s authorities have suggested the alarms are inducing panic and the situation is under control – even as the area posted a new record daily high number of deaths on Friday.

The authorities have been heavily criticised for allowing mass gatherings during local elections even as the country was recording global highs in the COVID-19 infection rate.

Our team travelled from New Delhi more than 200 kilometres to Agra and then several hundred more kilometres onto Lucknow – and all along the route, we found thousands of people flouting the lockdown and the night-time curfew only being patchily enforced.

It’s almost certainly contributed to the upsurge in infections and deaths over the past few weeks.

Although medics believe the situation is stabilising, there’s still an unknown number of infections and deaths throughout this large state which dwarfs whole countries in terms of population.

The sheer size of the state makes it difficult, if not impossible, to compile accurate figures.

A substantial number of the estimated 225 million residents in Uttar Pradesh live in remote, rural areas where there is little or no treatment for coronavirus.

A resistance to testing due to fear of isolating; the lack of access to hospitals or even clinics and an absence of co-ordinated monitoring of the COVID deaths has meant widespread scepticism about the official statistics.

Several doctors we spoke to from a variety of hospitals – in Delhi, Agra and Lucknow – are telling us the same information all the time about the virus and the variants.

This second wave is different; the variants are reacting differently and patients are developing some different symptoms.

Of course, there are important caveats. All of this information is anecdotal but with a fast-changing and developing disease, those on the frontline – especially in India – are anxious to share whatever they can glean about the disease and its changing make-up so others may be quicker to react or respond.

According to the range of doctors, nurses and health workers we’ve spoken to, there’s a marked increase in the number of patients who are suffering from body aches.

Often they don’t even have a cough but a fever.

The disease appears to be attacking a much younger age group but it’s not clear yet whether this is because the elder age group was the first vaccinated.

More patients are suffering from diarrhoea and eye infections and a very small number also suffer renal problems.

The variants appear to be more aggressive, seem to be more infectious and debilitate the sufferer far more quickly.

Dr Akhil Pratapsingh told us: “It seems the virus is more lethal this time…it seems so.

“Because the number of deaths are a little higher than last time…also what we are observing is last year it took some time for the patient to deteriorate but this virus, the infectivity or aggressiveness of the virus is so high it hardly takes a day for the patient, otherwise fine, to de-saturate and get compromised.”

In the crematoriums around Uttar Pradesh that we visited, all the workers spoke of a sharp increase in the number of deaths over the past few weeks although it now shows signs of plateauing.

But they also mentioned how the dramatic rise in funerals didn’t seem to match the official figures.

We watched as a sadhu (a Hindu holy man) performed a ritual around the many burning pyres at one crematorium.

He appeared to be the only person recognising the many dead people here.

We may never get an accurate toll of the pandemic dead throughout India.