“Incoming!”

One word and then Gosha’s life changed forever.

The mortar exploded right next to the 30-year-old Ukrainian soldier.

If his friend, Vasian, hadn’t shouted, Gosha wouldn’t have turned. The mortar would have exploded in his face. Instead it was his arm.

“Blood was streaming like hell,” Gosha recalls.

It was early May last year. The two friends were at the heart of a battle that would come to define the ferocity of the Ukraine war.

“I reached for my tourniquet and gave it to him. ‘Higher, Vasian!” He tightened it. It didn’t tighten well … and then he said ‘f***, what shall I do?’ I passed out.

“When I regained consciousness, I said: ‘Vasian, finish me off, because I’m f****** done'”.

Vasian wouldn’t do it. He refused his friend’s pleas. Sixteen months on, at a small prosthetics clinic in the United States, Gosha tells a story of horror and survival which reflects a much wider challenge.

At least 25,000 Ukrainians have lost limbs since Vladimir Putin’s invasion last year.

Accurate figures are hard to verify and could be much higher.

The number of Russian soldiers to have been maimed is not known but is thought to be huge too.

Neither Ukrainian nor Russian officials are willing, officially, to reveal a figure which underlines the cost of the war.

Read more:

In pictures: the pounding of Azovstal

The surgeon smuggled into Mariupol

Thousands of amputees

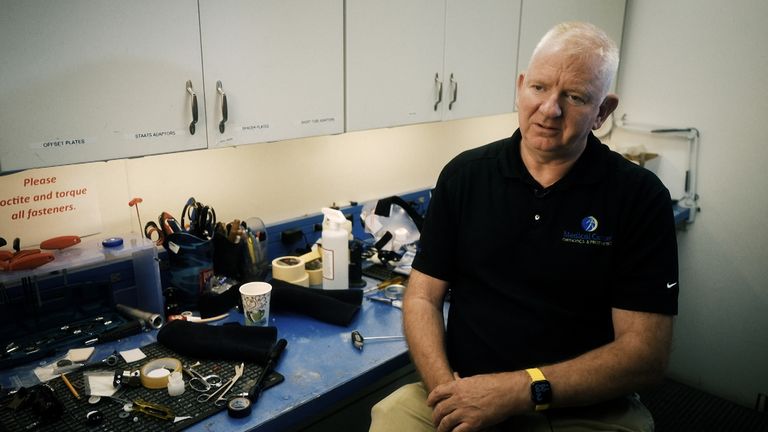

“The number is not official, and some of them are multiple limb loss,” Mike Corcoran, the clinic’s co-founder says of the Ukrainian estimate of 25,000.

“That’s a stadium full of amputees.”

In 18 months of war in Ukraine, there have been at least 10 times the number of Ukrainian amputees than Americans maimed over 20 years in Iraq and Afghanistan combined.

Gosha is the 39th Ukrainian soldier to come to the Medical Centre Orthotics and Prosthetics (MCOP) just outside Washington DC. We met him on the day he was first fitted with a prototype prosthetic arm. It is the start of several weeks of rehabilitation and therapy at the clinic.

Eventually, he will leave with a carbon fibre version of his missing limb.

The clinicians at MCOP are experts in military prosthetics and have spent two decades at the world-renowned Walter Reed Medical Center treating American soldiers.

But Ukraine’s challenge is different. It is compounded by the intensity of the conflict and rudimentary amputations.

The battlefield first aid straps, called tourniquets, designed to be attached to the limb just above the wound to stem bleeding, are often fitted too high and left on for too long. The bleeding is stopped but the cells in the limb are killed in the process.

The consequence – a whole arm or leg will need to be removed rather than just part of it. And that process is carried out in the most horrific of conditions.

‘The guys were rotting alive – it was like a horror movie’

Gosha was wounded in the battle for the Azovstal steelworks in the eastern Ukrainian city of Mariupol.

The two-month siege ended on 17 May, 2022 with the surrender of the last remaining Ukrainian soldiers. Gosha was among them and taken into Russian custody.

The battle was defining in its intensity and, ultimately, its futility.

Units from Ukraine’s Azov Battalion were cornered in one small part of the sprawling plant. The soldiers slept in an underground room which doubled as the battlefield clinic.

“People were lying together, one next to the other. They amputated arms and operated in the same room we were lying in,” Gosha recalls.

“They were cutting someone’s arm off. Everybody was watching it. On the floor there was a bag full of arms and legs.”

Gosha explains how the injured lay in a long narrow room lined with rows of bunk beds, three or four high.

“The guys were rotting alive, everyone was stinking, everyone had some infection,” Gosha says.

After his initial amputation in the bunker with a hack-saw, he said the wound “started to fester again” so his arm was amputated at a higher point.

Two weeks later, the steelworks was captured by the Russians. As a prisoner of war, Gosha spent more than a month without running water or painkillers.

He described how the ‘orcs’ – his slang for Russians – also took the Ukrainian soldiers’ supply of bandages.

He was finally released in a prisoner exchange. It marked the beginning of a long journey which has brought him, for a few weeks, to America.

‘You can’t say no’

The MCOP clinic does not charge for its treatment of Ukrainian soldiers and prosthetics is an expensive business. One arm can cost $100,000 (£81,000) and a hook in place of a hand is an additional $8,000 (£6,500). A lot of Ukrainians ask for the hook because it’s more versatile.

“You can’t say no”, says Mike.

The fortunate fraction of Ukrainians who make it here to MCOP do so with the assistance of many charities including United Help Ukraine and Operation Renew Prosthetics in partnership with the Brother’s Brother Foundation.

The plan, eventually, is to open a clinic inside Ukraine. For now, Mike and his team are shuttling back and forth to Ukraine to train locals, deliver donated equipment and conduct in-country treatment.

“It’s going to take more than our company and me. It’s going to take hundreds of prosthetists many years to actually take care of all these wounded people, not just military, civilians as well,” Mike says.

He predicts the challenges Ukraine faces with amputations will, eventually, make it the world leader in prosthetics. But it will take time and huge investment.

The growing list of people with lost limbs will, Mike said, “have to be addressed at some point”.

The limits of US aid

The US government has supplied billions of dollars of weaponry in tranches of ‘security assistance packages’ for Ukraine. But these packages do not allow for the funding of treatment or sharing of medical resources to treat injured Ukrainian soldiers.

In a statement, a spokesman for the US Department of Defence (DoD), Lt Colonel Garron J Garn, said: “DoD has not received any specific requests to enhance prosthetic care for wounded Ukrainian service members.

“However, there are several members of Ukrainian Armed Forces currently at Landstuhl (a US military medical facility in Germany) receiving treatment, outside of specific prosthetic care. We applaud the work of various charities who are involved in getting Ukrainians requiring prosthetic care.”

Colonel Garn added that $14m (£11.3m) had been “obligated to support wounded service members of the Ukrainian Armed Forces for its budget in 2023”.

As Mike Corcoran and I talk, another Ukrainian arrives for his final appointment at the clinic.

Ilia Mykhalchuk is a double amputee and is ready for his final fitting of two state-of-the-art carbon fiber arms.

His story is horrific. One arm was blown off and the other peppered with shrapnel after an anti-tank rocket hit his vehicle in another defining battle of this war, in the city of Bakhmut.

The 36-year-old was then captured by Russia’s notorious Wagner Group of mercenary fighters.

“They knocked him out with whatever anaesthesia they had in the basement of a house,” Mike said.

“Basically it’s like a guillotine. They cut off both his arms and they didn’t even close them up, they just bandaged him. So it wasn’t clean; just the bone. The cut end of the bone is protruding and that makes for a harder fitting.”

The scars left by the Wagner Group are both physical and mental.

“They made fun of him after they cut off both his arms. He saw torture, men being set on fire and having their fingers cut off. He’s got a lot of PTSD,” Mike said.

Watching Ilia, as the final fitting is completed, that internal trauma is clear.

‘He never leaves my head’

Back in conversation with Gosha, more revelations which reflect the reality of this war and his ongoing trauma.

I asked about his friend Vasian – the comrade who had called out ‘incoming’ and had saved his life.

Gosha reveals that Vasian, and his pet dog, who was their companion in war were taken by the Russians and have not been seen since.

“Vasian never leaves my head,” Gosha said. “He is my sworn brother.”

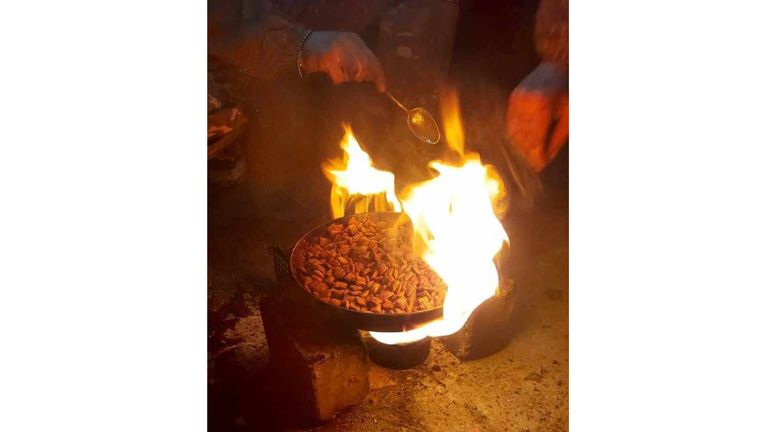

Gosha explained how he, Vasian and the dog, a Pit Bull Terrier called Sofa, would share dog food. It was all they could find in the sprawling steelworks. They would cook it. “It didn’t taste bad,” he says.

“We made beds for ourselves, and we put the dog between us, in the middle, and we slept like that, hugging. The dog could get some warmth. We were always together. And I promised him: “When we return back home, when I baptise my son, you will be the godfather.”

“My son is five now, he has not been baptised yet because I’m waiting for Vasian to return.”

Gosha wants to go back to the frontline. “I want to fight, if it’s possible, as a gun commander in the artillery.”

“Nobody wants to live in captivity. Russia will continue to terrorise, kill, capture, destroy. They won’t calm down until you beat the f****** hell out of them.”

With additional reporting by Eleanor Deeley, US Producer