PORT ORCHARD, Wash. — A Mexican super cartel brought its deadly drugs and violence to the tranquil and remote waterfront community of Port Orchard, a 90-minute ferry ride west of Seattle.

Here, the Kitsap Peninsula, billed as “the natural side of Puget Sound.” attracts hikers, bikers, golfers and boaters — and members of a top U.S. target, the Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación.

The cartel, known as CJNG, set up a meth conversion lab here years ago as part of a Western Washington drug cell that pummeled the region with millions of dollars worth of heroin, meth, cocaine and fentanyl-laced pills.

Standing near the chilly waters of the Sinclair Inlet during a recent interview, Police Chief Matt Brown described how Port Orchard’s police force of 23 is outnumbered in the struggle to safeguard the town’s nearly 17,000 residents from international drug networks and deadly fentanyl.

The situation he described contrasts with the image across the water on the opposite bank in Bremerton, home to the sprawling Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, providing maintenance and support to help assure U.S. “dominance at sea.”

“We no longer have a drug task force” in Port Orchard or Kitsap County, said the chief, who considers it “absolutely” concerning.

Selecting a town like Port Orchard, 28 miles northwest of Tacoma, is indicative of a key CJNG strategy to reach its tentacles deep into small, unexpected corners of America.

“They chose places that may not have a large law enforcement presence, and places people wouldn’t expect cartels to be operating in — in the beautiful community of Port Orchard on the water,” said Tessa Gorman, acting U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Washington, headquartered in Seattle.

A Tacoma-based task force, led by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, stumbled onto CJNG’s drug ring in 2019 and secured authorization from a federal judge to perform wire taps, monitoring more than two dozen phones for 18 months.

Investigators soon learned the drug ring’s crimes stretched to several West Coast communities and south into Oregon and California.

“It wasn’t until six months into the investigation until we knew how big it was, because it just kept spider-webbing and spider-webbing, getting bigger and bigger,” said Luke Brandeberry, who worked on the case as a DEA task force officer.

“The drug ring we were investigating, CJNG, the Cartel Jalisco New Generation, is notorious for the amount of violence they would use down in Mexico, as well as locally here in Washington,” he said.

Gorman, who oversees all federal prosecutions in Western Washington, said the investigation unearthed a massive drug network that stood out for its savagery. She said the violence drug ring members were willing to use to protect their business, was “extremely disturbing.”

“There were kidnapping plots, there were shots fired, there were talks about torture, including cutting off hands,” Gorman said. “That level of violence in our community is terrifying.”

The Louisville Courier Journal, part of the USA TODAY Network, traveled to Seattle, Tacoma, Kent and Port Orchard in November to interview police and prosecutors and sift through court records to learn more about the violent CJNG drug ring that targeted Western Washington. This report is part of an ongoing project that began in 2019 with a nine-month investigation on CJNG and its key role in the deadliest drug epidemic in U.S. history.

Americans tend to know more about CJNG’s top rival, the Sinaloa Cartel, and its infamous former kingpin “El Chapo,” but CJNG is the other dominant cartel pummeling the U.S. with deadly drugs, according to DEA reports.

CJNG’s leader, “El Mencho,” has remained on the run in Mexico for more than a decade, despite a $10 million reward for tips leading to his capture.

In Washington, CJNG put Juan Antonio Gonzalez-Carrillo, known as “Toto,” over the drug ring and he often “fronted” drugs — allowing local traffickers to take the drugs on loan and repay him later, prosecutors allege in court records. Some dealers began to use drugs themselves, running up big tabs, while others were robbed or lost drug shipments during police traffic stops.

Back in Mexico, CJNG leaders grew angry. They sent cartel supervisor Alan Gomez-Marentes to take the reins of the drug ring and oversee debt collection. After a territorial dispute, Toto left the area and resurfaced in California. A grand jury in Seattle indicted him in 2020 on drug trafficking charges, but he disappeared. Police aren’t sure if he’s in hiding or dead.

Marentes left his home in Zapopan, west of Guadalajara in the state of Jalisco, CJNG’s headquarters, unaware of the trouble awaiting him in the U.S.

Marentes headed to Washington and settled in the Kent area of King County, between Seattle and Tacoma. During phone calls with underlings, he openly boasted about his close ties to top CJNG leadership and his new role as the boss of the Washington cartel cell, said Brandeberry, who overheard the conversations while monitoring wiretaps.

Marentes didn’t know investigators were listening as he revealed details about specific drug shipments and revenge plots — words that would come back to haunt him.

“There were several times we had to jump in the middle of something because we found out with five or 10 minutes to spare, that someone’s about to be killed, kidnapped or shot,” Brandeberry said.

The drug ring’s muscle, Luis Arturo Magana-Ramirez, who lived in Fife, Washington, often chatted about plans to abduct, harm or kill debtors as agents monitored the calls or texts, according to Magana-Ramirez’s plea agreement.

Investigators would have to rush, often rousting the lead case prosecutor from sleep, to ask for guidance. They didn’t want to prematurely blow up their investigation, but they didn’t want anyone to get hurt.

“It’s a really hard balancing act for officers and prosecutors,” Gorman said. “You’re walking a tight rope every day. They are constantly assessing when to intervene.”

Sometimes, police didn’t have enough information ahead of time to prevent kidnappings and beatings and other violence.

For instance, investigators were going to arrest a local street-level dealer, but couldn’t find him. The man, who owed the drug ring money, vanished. Brandeberry, who had bought drugs from the man while working undercover, said information learned during the investigation indicates the man was murdered and his body dumped somewhere in a vast, wooded area of south King County.

Another time, drug ring member Jose Elias Barbosa attempted to seize a woman’s car because she owed a drug debt. Someone stepped in and shot Barbosa in the collarbone in the November 2019 incident outside the Port Orchard meth house, which was near a shopping center. Barbosa survived but refused to identify the gunman, so the case remains unsolved.

He ended up in danger again, and this time police came to his rescue.

Magana-Ramirez offered another drug ring member $10,000 for Barbosa’s head. At the time, no one could find Barbosa, so another plan was hatched to kidnap Barbosa’s brother-in-law and cut off the man’s hand, which would be sent in a box as a warning to Barbosa.

Barbosa resurfaced, so police rushed to arrest him at a Mexican restaurant in Kent to prevent his murder. As officers arrived, they spotted suspicious men in a BMW watching the restaurant and believe the men had been waiting for the chance to snatch Barbosa.

Somehow, Barbosa’s brother-in-law learned of the murder plot and successfully convinced relatives in Mexico to lobby cartel leaders to spare him and Barbosa.

CJNG often sends boxes of hands or even heads to victims’ relatives in Mexico as a way to rule by fear. But CJNG and other cartels typically avoid “spill over violence” across the border because it draws too much attention from U.S. police.

But this drug ring continuously plotted acts of violence in Western Washington.

In Port Orchard, when agents raided the meth house after Barbosa was shot, they found 15 guns, along with heroin and cocaine. They also found 1,700 fake prescription pills laced with fentanyl, of particular concern as DEA testing indicates seven out of every 10 pills on the streets today contain a potentially lethal dose.

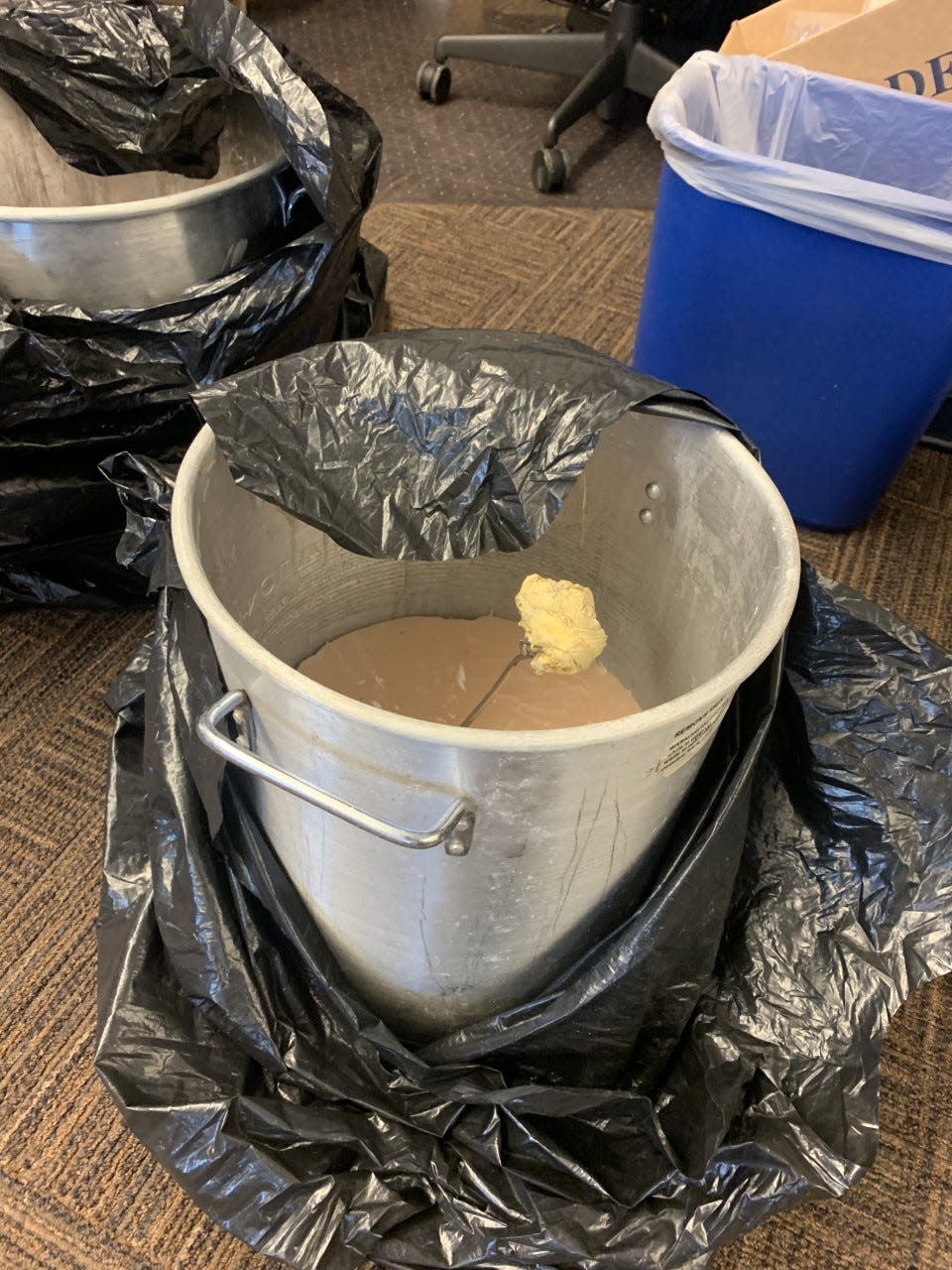

Inside the house, police also found 120 pounds of methamphetamine, including meth-infused candles. Cartels are increasingly sneaking meth into the U.S. in liquid form, hidden in candles, gasoline or windshield wiper fluid.

CJNG’s Washington cell routinely gave shipment orders to a cook in Mexico, who infused candle wax with liquid meth. Once the candles arrived at the home in Port Orchard, drug ring members extracted the meth and turned it back into a solid. Traffickers then packaged the product, in hard, clear chunks that resemble rock candy, to sell to customers.

In April, 2020, Magana-Ramirez described revenge plots against those who owned money for drugs, saying one man “needed a beating.”

Magana-Ramirez told a drug ring member to “gather as many toys as you can,” referring to guns, “so I can take them down,” according to his plea agreement.

“This is about me getting, grabbing them and tying them up with a strap like a [expletive] dog.”

Marentes and Magana-Ramirez were among about two dozen drug ring members or associates arrested in July 2020. All ended up pleading guilty.

In sentencing memos for some of the key drug ring members, prosecutors attempted to describe the harm they had done to the community. The assistant U.S. attorneys cited overdose data for King County, home to Seattle and Kent, which was averaging 17 deaths a week from overdoses, mainly from fentanyl.

Marentes admitted the drug ring trafficked at least 78 kilos of meth, more than two kilos of heroin and 930 grams of fentanyl, according to his plea agreement. Considering an amount of fentanyl as small as 2 milligrams can kill, Marentes’ drug ring brought in an estimated 465,000 potentially lethal doses.

A judge in Seattle sentenced Marentes to serve 11 years in federal prison, where parole is not an option, noting Marentes’ prior federal conviction for drug trafficking.

A month after the arrests in 2020, Brandeberry left the DEA task force and returned to patrolling the streets of Kent, forcing him to confront his own town’s casualties of international drug trafficking.

“It seemed like every day there was an overdose — just me and another officer with a body in the street, trying to bring them back, trying to find their ID and trying to find their next of kin,” Brandeberry said.

“You forget about how many grieving mothers and fathers there are in the country dealing with a lost loved one because of this.”

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: CJNG cartel targeted tranquil Puget Sound city with meth, fentanyl