Welcome to another edition of Pass/Fail, where I take on the question of how well a comic/graphic novel is adapted for either large or small screen. I’m not reviewing adaptations here (though opinion does sneak in from time to time); what I am doing is looking at how well either the spirit of the original property is explored or how well the writers/producers/actors/etc. literally lift the comic from the pages and splash it across your viewing device of choice.

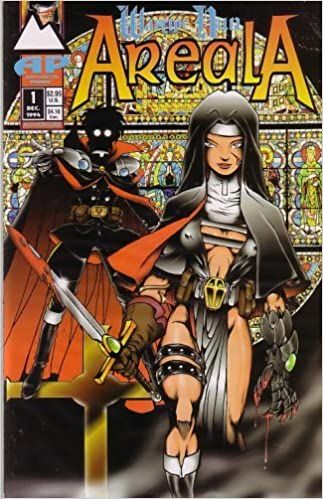

Full disclosure: this Pass/Fail is going to be somewhat third hand; I’ve been poking around to see if I could get my hands on some of the original Warrior Nun: Areala comics from 1994 (the character first appeared in Ninja High School #38—yes, Ninja High School, and yes, there were at least 38 of them—in 1987). I found it, but the cheapest copy was $60 and I love you guys but I’m not paying $60 for a single issue of a comic with extremely questionable art (my autocorrect thinks her name is Warrior Nun Areola and I…cannot disagree), so to the internet for synopsis we go, sorry.

Anyway…

The Comic

Warrior Nun: Areala tells the story of the Order of the Cruciform Sword, founded in 1066 (probably because that’s one of the only years in European history everyone learns about) by a Valkyrie named Auria (later Areala) who turned to Jesus for salvation. In each generation, Areala chooses an avatar to lead the Order, a group of warrior nuns and magical priests, who fight in the service of the Catholic Church. For the first 20 years of the comic’s on-again, off-again run, that avatar was Sister Shannon Masters.

The Order of the Cruciform Sword is purported to be based on a historical group, The Fraternity of Our Lady, who established a chapter in New York in 1991 for the purposes of founding a soup kitchen but who also learned martial arts and self defense to be able to protect themselves in the city. Dunn, Areala/Shannon’s creator, said he drew on an article about the Fraternity to create “a true hero, not an anti-hero…she doesn’t kill people, only demons…She believes everybody can be saved.”

In the comic, Sister Shannon is the central figure around whom the other characters orbit. Though she sometimes doubts herself, she doubts neither her faith nor the family she found in the Order. Orphaned at the age of 4, Shannon was left on the steps of a convent; she was eventually adopted by a Japanese family with whom she lived until she turned 11, at which point her athletic and academic skills earned her a place at Saint Thomas Academy. It was there that Shannon was trained as a Warrior Nun. She becomes Areala’s avatar after almost being killed in a battle with a Satanist/arms dealer, which…seems like a thing someone could be.

The Show

The BFF and I are tandem watching the Netflix adaptation of Warrior Nun and we’re only about halfway through so it’s entirely possible that opinions I render here and now will be moot for those who have already finished; apologies in advance. I’ll also avoid major spoilers for those who are behind us.

Warrior Nun is a “spirit of a property rather than a literal translation” project, and that was good call on several levels. The most obvious of which is there is no way in HELL (irony intended) I’d watch a show where nuns, warrior or not, were dressed like our friend in the aforeposted picture. I would not, in fact, watch anything in which the women were dressed like the one in the aforeposted picture, because that outfit is objectively gross and also not stopping a bullet, not stopping a blade, not stopping a damned fingernail. These ladies are fighting demons, not baby chicks or tribbles. Jesus take the wheel.

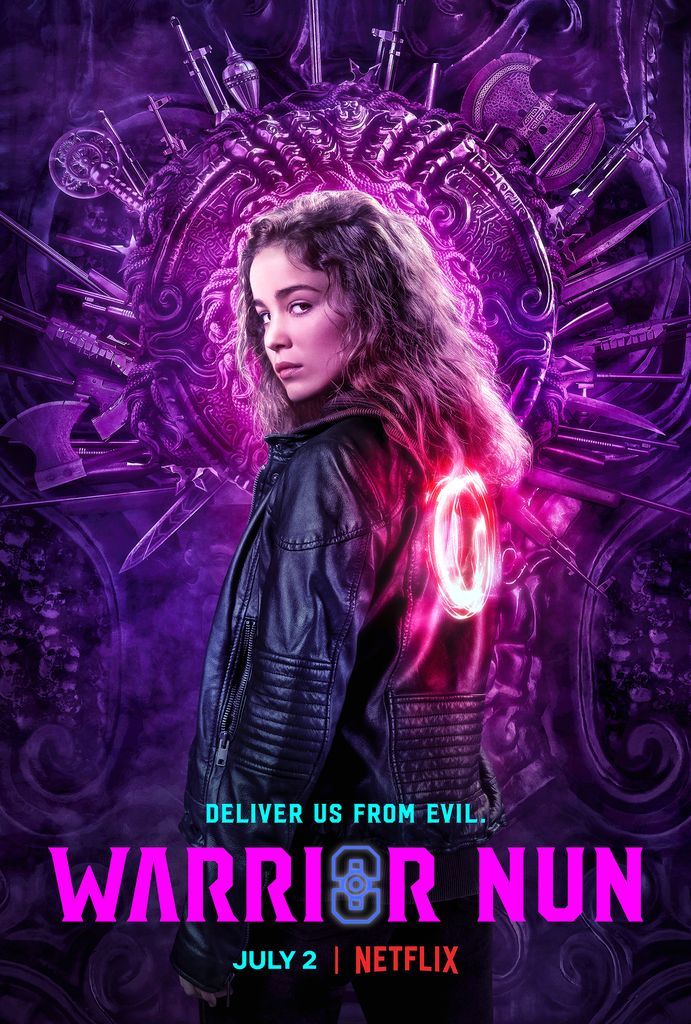

Behold practical armor for the battle nun who might actually live to see tomorrow, which is probably smart in a world where not that many women want to be nuns:

The show also introduces a new avatar to the mythos: unlike Shannon, Ava Silva hasn’t isn’t a trained badass. Until the moment she wakes up from the dead as Areala’s chosen one, she has in fact spent the majority of her life being “cared for” (read: berated, yelled at, and mocked) in a Catholic orphanage after the car accident that killed her mother left her quadriplegic. For Shannon, who’s been on a 20-year magical mystery tour, there’s nothing new under the sun; for Ava, able to walk again after over a decade and for the first time as an adult, everything is new and all the stakes are high. She is invested in everything, which charges the story with an urgency Shannon’s years of experience likely wouldn’t have been able to capture. I do see some potential issues with disability rep here, and I’d be interested in having the writers explain why they felt that particular transition was one it was so important for Ava to make when there were other options.

I also appreciate that The Order of the Cruciform Sword in the Netflix incarnation of Warrior Nun is made up entirely of women, with the exception of a single priest who acts as confessor and liaison between the Church and the Order (can’t have those women liaising for themselves, never know what trouble they might get in it). So much of the media we consume insists on falling back on the tired trope of women being unable to exist as a cohort without testosterone, that we need to backstab and bicker like we need to breathe. Is it all kumbaya and prayer candles in the nun fort (there is actually a nun fort)? Absolutely not. But there is a group of smart, strong women who see the world for what it is and understand that the only people who are going to protect them are their sisters in the cloth and the sisters they have chosen, who happen, in this case, to be one in the same.

Warrior Nun is for sure a little bit silly, and if having to suspend your disbelief on the logistics of international travel drives you to distraction you may want to sit this one out. But as “spiritual” adaptations go, I give it a firm pass at least as far as I can with what I have. Like I said, I love you guys, but I don’t Warrior Nun: Areola love you. At least take me to Valhalla first.