The great irony of Diana, the late Princess of Wales, was simple: She was as much a creator of media as she was its creation. The British press might have forced the blushing teenaged “English Rose” to blossom, but Diana’s own tactics are why, 24 years after her tragic death, multiple award-nominated celebrities are playing her. In the decades since the young Diana Spencer crept down the aisle in an overflowing taffeta wedding gown, more than a dozen actresses have attempted to match her magnanimity. Madonna tried it. Naomi Watts tried it. Most recently, Kristen Stewart has tried it. And as one of the first and only films about the late princess to achieve critical acclaim, Stewart’s Spencer begs the question: What happened differently this time? And have we finally reached the pinnacle of Diana’s clutch on pop culture?

Perhaps it is not, in fact, an irony but a triumph that Diana is still under the microscope today. As journalist Tina Brown wrote in her 2007 biography, The Diana Chronicles, the princess’s “life’s obsession” was controlling her publicity: “The camera was Diana’s fatal attraction…It had created the image that had given her so much power, and she was addicted to its magic, even when it hurt.” Diana’s former bodyguard, Ken Wharfe, agreed within his own memoir, Diana: Closely Guarded Secret, saying she “craved public recognition almost as much as she cherished her privacy.” There’s little question, then, whether the princess would relish the attention still lavished upon her, from the prestige performances of Emma Corrin and Elizabeth Debicki in The Crown to the jovial spectacle of Jeanna de Waal’s dancing in the maligned Diana: The Musical. Diana isn’t here to mold her mythology anymore, but it has nevertheless earned a life of its own. And not all who have steered it in the years since her death are proud of it.

Hollywood’s addiction to the princess started before she’d even settled into wedded life with Prince Charles, and the obsession—like her marriage—seemed plagued from the beginning. A year after the couple’s lavish ceremony at St. Paul’s Cathedral, two dramatizations of the wedding arrived on cable: On CBS, it was The Royal Romance of Charles and Diana, starring Catherine Oxenberg, and on ABC it was Charles and Diana: A Royal Love Story, with Caroline Bliss in the princess’s role. The Washington Post slammed the CBS special as “slack-jawed heraldic voyeurism,” while the New York Times criticized ABC’s for its “generally competent actors uneasily trying to impersonate well-known central figures.” Neither argument could stop the plates from spinning now that they’d begun.

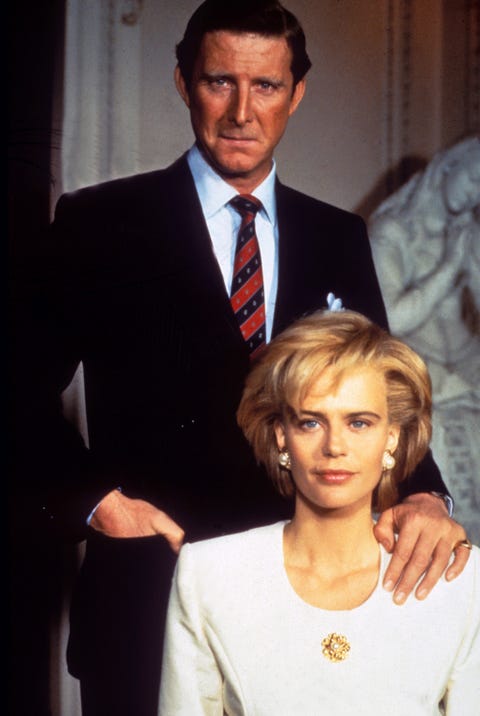

A short gap followed. It took another decade for the “good-looking but unabsorbing rehash” The Women of Windsor, in which Nicola Formby played Diana, to arrive. But it wasn’t until the following year, in 1993, that Serena Scott Thomas took on Diana: Her True Story, adapted from Andrew Morton’s earth-shattering book, in which the princess revealed the extent of her bulimia and self-harm, as well as the shocking circumstances around her collapsing marriage to the Prince of Wales and his infidelity with Camilla Parker-Bowles. If the book was a lightning rod for controversy, then the film certainly would be, too. But Scott Thomas accepted the role, she says, out of “youth and stupidity.”

Today, the actress doesn’t talk about the film much; in fact, this is the first interview she’s agreed to in years. “I avoided it for a long time,” she says. “It was only when I started thinking about how the film that we [did] was considered so scandalous, versus the frightfully proper and extremely well-received The Crown, for example. When I thought about the difference between those, I started to have these uncomfortable feelings. Because I’ve never really had to address it before.”

Scott Thomas, then in the early stages of her acting career, had “about a week to prepare” after accepting the role. The film was on a fast-track due to the media frenzy around its source material, and days on set were grueling. Most nights, she returned to her hotel room alone to memorize pages upon pages of dialogue and attempt to corral the mop of blonde hair glued into a coif on her head. The script, she admits, was “pretty terrible,” but there was “excellent” lighting, talented hair and make-up artists, and “the director was a honey.” None of that ended up making a difference: Critics panned the film, but viewers tuned in by the dozens. When Diana: Her True Story debuted in Britain, it earned the highest ratings that broadcaster Sky TV, then in its third year, had ever received.

Scott Thomas had known the project would be an audience success. (She spotted the paparazzi hiding in the bushes while she was on set.) But the critics made her queasy—“it’s awful when people write horrible things about you; it’s extremely hurtful”—especially when, years after she’d moved to America and left the film behind, reporters continued to attach her name to Diana’s. After the princess’s death, producers returned to Scott Thomas and asked if she’d do another film. She shut them down.

“I didn’t think things through [when I accepted the role],” she says. “Did it affect my career? Most definitely. But [above all], I do feel a great deal of remorse. I really do feel badly for having been a part of something that caused pain to [the royal family], who do nothing but work their butts off for us. Would I do it again? No.”

It’s been years since Scott Thomas, who later appeared in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Nip/Tuck, wore the Spencer name, but the Diana Cinematic Universe continues to fascinate her—in part because its perception has transformed from frivolous to finessed. When Diana: Her True Story debuted, Scott Thomas was pegged as a non-serious actress, superficial for taking on the princess’s weepy tale of a fairytale gone wrong and, worst of all, invasive for butting into a family’s private matters. But today, the same story is an Emmy and Oscar gold mine. “Now they’ve got the finest actors and the massive productions, and it’s all frightfully kosher,” Scott Thomas says. “When I did it, it was like, ‘Oh, off with her head.’ It’s very interesting how it’s changed.”

The shift didn’t come until well after the Paris car crash that took Diana’s life, and even then the path to a quality film was winding, perhaps even cursed. In 1998’s Diana: A Tribute to the People’s Princess, only a year after Diana’s death, Amy Seccombe took on the first posthumous depiction of the princess in a production deemed “unconvincing” and “ill-advised.” Producers didn’t try again until nearly 10 years later, in 2007, when Richard Dale, an Emmy- and BAFTA-winning director, released the docudrama Diana: Last Days of A Princess, which intermixed dramatizations with real-life interviews. The Times dubbed it “as convincing as it is cheesy,” so “over the top, it sucks you in right away.”

Dale took the matter seriously, even if the surrounding media did not. Today, he thinks of the piece as part of the historical record, a time capsule revealing how the princess’s death jangled traditionally unshakeable British sensibilities. “It seems hard to believe now that The Crown is everywhere, but [back then], the idea that you could actually, realistically portray the royals was new, and it really wasn’t considered either proper or useful,” he says. “It sounds silly, but that many years ago, it wasn’t as easy.”

Even as recently as 2013, a cloud loomed over anything the entertainment industry dared imbue with Diana’s touch. That was the year Oscar-winning actress Naomi Watts starred in the disastrous Diana, based on the book Diana: Her Last Love by author and former BBC and Channel 4 executive Kate Snell. Watts, normally so striking on screen, was rudderless within the painful script and bleak cinematography, washed out in cool tones and cooler line delivery. Meant to demonstrate the sweeping romance between the heart surgeon Dr. Hasnat Khan and the late princess in the years following her divorce from Prince Charles, instead Diana delivered clunky jokes—“Pretty hot stuff, eh? You, in the kitchen” stands out—and lacked chemistry between its lead actors. The result was so catastrophic, so hated by critics, that Watts herself has referred to the film as a “sinking ship.”

Snell, herself now creative director at the Serbia-based Firefly Productions, looks back on this development as sad, but not altogether shocking. When you pass off the rights to adapt your book, there’s no guarantee of what might happen to it. She’d stumbled into the story of Khan and Diana while watching the princess’s funeral footage, where she found a man wearing dark glasses and standing alone. That one image sparked months of research, and a lifelong respect of the woman who dared defy the monarchy in the pursuit of love. But Snell understands, perhaps better than most, how much it takes to get Diana’s story right. The princess was a chorus of paradoxes: devoted in partnership but vicious when scorned; empathetic to all but ruthless to herself; coy but playful; joyful but haunted; adrift but tactile; adoring to her sons, Princes William and Harry, but inevitably inclined to self-destruction.

“From the moment she emerged onto the public stage, she was like Botticelli’s Birth of Venus,” Snell says. “I just don’t think there’s anybody who’s going to fill her shoes. There hasn’t been anybody since and there’s nobody on the horizon either. So she occupies a very, very unique place in our society.”

Perhaps the trickiest characteristic for any actress to nail is Diana’s ubiquitous warmth. Virtually all who encountered her liked her, if they didn’t outright fall in love with her. She existed in an age that predated social media, when—even with the ravenous press documenting her every move—she could float in a bubble of adoration without live-tweeting her own downfall. She was pre-“cancel culture,” pre-Brexit, a sort of avenging angel of ’90s optimism. She championed the AIDS cause and a ban on landmines. She looked like a beauty queen, wore high-waisted jeans and off-shoulder gowns with equal panache, and she could empathize with a people who lived far from her orbit.

Royals reporter Kinsey Schofield, who operates the popular blog To Di For Daily, puts it this way: “We live in a society today where the only way to be famous or successful is to be polarizing. Look at [Prince] Harry and Meghan [Markle]; people either love them or they hate them. That’s how you go viral. That’s how you get attention online. And with Princess Diana, she is one of the unique characters in our universe right now who was just generally adored.”

That enduring innocence is part of why now, nearly a decade after the Diana film’s fall from grace, there are no less than four recent projects about the princess, all streaming or playing in a theater near you. They range from the Lifetime Harry & Meghan films, in which New Zealand actress Bonnie Soper plays Diana, to the prestigious Kristen Stewart-led film Spencer and Netflix’s The Crown, both contending for (and, in The Crown’s case, winning) major awards. Notably, most of the actresses playing the Princess of Wales demonstrate little to none of the doubt or regret that trailed those who came before them.

“Oh, I love it,” Soper says, when asked if she’d continue playing Diana beyond her three appearances in the Harry & Meghan films. “I just want to do it more. I want a movie just all about her.” Stewart showed a similar eagerness around Spencer. “Even if people hated it, and it ended up being like a sort of misfire…this wasn’t something I could pass up,” she told Reuters. “I had to give it a shot.”

Even the Broadway musical starring de Waal—mercilessly panned by critics when a filmed version hit Netflix in October—has achieved something like cult loyalty. Critic Peter Bradshaw was prescient when he predicted “masochists getting together for Diana: The Musical parties, just to sing the most nightmarish lines along with the cast.” Now that the show has officially opened on Broadway, audiences are embracing the technicolor joy of it all, whether it’s Diana’s lover James Hewitt riding in shirtless on horseback or the cohort of trench-coat-draped paparazzi singing, “Better than a Guinness, better than a wank/Snatch a few pics, it’s money in the bank!” As New York Post writer Johnny Oleksinski put it, “It’s so campy you circle the date [of the performance] on your calendar in glitter pen.”

This article is far from the first to ask why it took so long to get solid Diana stories on the screen. Arguably, it was The Crown’s success that first opened the floodgates, a fact Corrin seemed to understand before she made her debut on the series. “I remember, when I got the part, Benjamin Caron, the producer, said: ‘Life’s going to change a lot when this comes out,’” she told the New York Times. Before The Crown, she was a relative unknown; now, she’s an Emmy-nominated celebrity starring in blockbusters opposite Harry Styles.

Even on less glitzy productions, the fanaticism can be startling. The first time Soper played Diana in 2018’s Harry & Meghan: A Royal Romance, she figured no one would even notice her brief appearance in a flashback. “I had no idea what was going to happen afterwards,” she says. “It was all of this interest and attention. I was like, ‘Oh my God.’” Passions only surged after Prince Harry and Markle announced they’d be stepping away from royal duties, igniting the firestorm that culminated in a dramatic interview with Oprah Winfrey. It was as if, now more than ever, the whole world could see Diana’s hand on her son’s shoulder.

So now we come to Spencer, arguably the most unique of the bunch for its snapshot approach to Diana’s tragedy. After watching every piece of Diana-centric media he could track down, Jackie director Pablo Larraín realized there was an opportunity to tell a “fable” orchestrated through Diana’s own viewpoint. “I understood that we had a chance to do something that has not been made in the same way,” he says.

So, Spencer would go inside the princess’s head during a particularly chilling Christmas at the royal estate of Sandringham, where everything from the set of scales in the foyer to the “They can hear you” signs in the kitchen seemed designed to provoke her bulimia and depression. The film would not attempt the range of a biopic, nor would it draw from a specific scene mentioned in any of Diana’s real-life interviews. It would be a sort of autofiction, to draw from the literary world’s term for a novel infused with an author’s lived experience. And the film would star Twilight actress Stewart, an all-but-obvious pick to play the People’s Princess.

For Spencer writer Steven Knight, the allure of the story was, in fact, its troubled history in Hollywood. “That it was almost set up to go down the same road as all the others made me want to do it,” he says. “You want to challenge yourself to do things.”

While most critics have applauded Stewart’s performance, others have criticized its melancholic, sotto voce approach as antithetical to Diana’s own glowing, overflowing personality. But what’s fascinating about Spencer is how it sets aside the way Diana was publicly perceived—as the princess herself once said, “Even when I am feeling like hell I can pretend”—but peers into how she actually felt behind the walls of the castle. As Brown wrote in The Diana Chronicles, “Pain made her luminous…Diana’s tantrums, her bulimia, her whole crazy drama—it all feels today like a furious desire to repudiate not just her Windsor present but her Spencer past. All of it—the whole bill of goods she’d been sold as a female from the moment she’d been able to gaze up fetchingly at her father’s camera…she wanted to vomit it all up, tear it up, hurl it into a pit of fire. That’s what all the screaming and cutting and bingeing and starving was about. She would be her own Frankenstein’s monster, and nobody else’s.”

That woman, the one who wore the “revenge dress” that’s launched entire Instagram fan accounts, is a woman who resonates in 2021. A woman, shaken and perhaps disturbed, who rattles the bars of the cage and prays for a better, more beautiful world. That’s a woman who can become a Hollywood icon nearly a quarter of a century after her bodyguard’s car hit a concrete pillar at more than 65 miles per hour in Paris. Diana was a creation of media, but she learned to steal back the camera, and in the bloody fight to do so, she won her own legacy.

With the next season of The Crown set to premiere in 2022, in which Debicki will take the reins from Corrin, the question stands whether we’ve finally reached the apex of Diana content—and whether or not it’s right to keep going. August 31, 2022, marks the 25th anniversary of her death, and The Crown will end after the next two seasons. Surely, now with the Sussexes settled in America, and Prince William’s coming kingship all but guaranteed, the fervor around the boys’ mother might flicker and die out. Perhaps it even should. But many of the actresses, writers, filmmakers, or experts interviewed for this piece agreed: Diana’s story is still on its upswing.

“What I think is going to happen is that there [will] be a lot more coming,” Larraín says. Adds Knight, “Anyone who has passed on makes no mistakes. And so therefore, the admiration grows. Nothing can happen that’s going to stop her.”

At the suggestion audiences might grow weary of Hollywood’s numerous attempts to resurrect Lady Di, Schofield even laughs. “I enjoy these stories. I eat them up. I don’t understand people that say it’s morbid or that it’s oversaturated,” she says. “I don’t agree. And I think Diana would love it. I hate to say this, but I think Diana would love it because she wants to remind Charles and Camilla of it. People still love her.”

There are still plenty of projects left to take root around the late royal’s life, Snell argues. Many of the creators behind the Diana productions of yore skew male and mostly white. “I’d love to see an all-women’s team come together and really make something interesting that unlocks her psychology a bit more,” she says.

It remains to be seen whether Diana’s posthumous charisma can continue to draw tickets, clicks, and streams, and more importantly if her status alone is enough to draw quality talent. But it’s 2021, and her name is still on the marquee. Everyone still wants to play her, write about her or dress like her (or, best of all, some combination of the three). Both her sons have named children after her. Brown wrote in The Diana Chronicles that Diana’s quest for happiness was “unplanned and unfinished,” but it seems, now more than ever, so is her story.

The Diana Cinematic Universe might not match the magnitude of Marvel’s, but the IP is more precious, more authentic, and the real-life results more keenly felt. Diana has already transformed one troubled system from the inside. Perhaps, with a loving, careful touch, she can do the same for another.