Higher costs, more paperwork and border delays have been “the only detectable impact so far” of Brexit for British businesses, according to a new report by MPs.

Trade volumes have been suppressed since the end of the transition period in December 2020 – though the COVID-19 pandemic and wider global issues were also key factors, the report said.

But the Commons public accounts committee (PAC) said it was clear that Brexit has had an impact and called for the government to calculate the additional costs that firms face.

New burdens include having to pay for help to complete customs declarations as well as fees due to the government and port when some goods are selected for physical inspection.

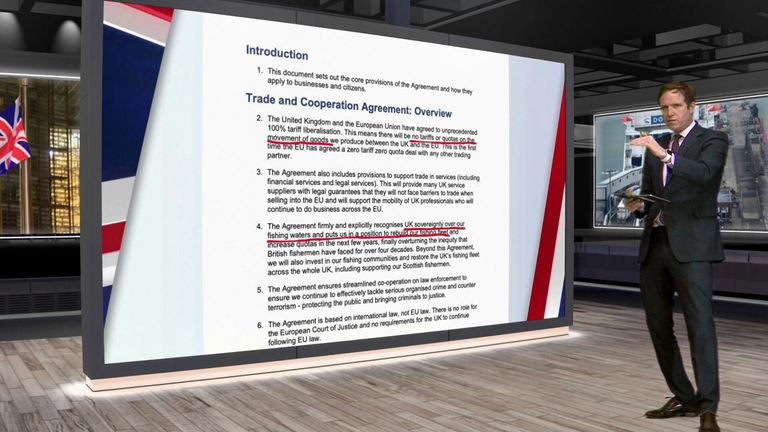

Traders also face tariffs if goods do not comply with “rules of origin” requirements. Britain’s free trade agreement with the EU is on condition of certain products being traded having a minimum proportion of their “origin” in the exporting country rather than coming from somewhere else.

Making sure they are in compliance with new rules also adds costs, the committee said.

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) estimated in 2019 that the extra administrative burden on businesses on UK-EU trade would add up to £15bn a year.

The MPs said that while this had yet to be updated, HMRC had told the committee in November that there were “indications that the costs to businesses will be less than that estimate”.

Dame Meg Hillier, chair of the public accounts committee, said: “One of the great promises of Brexit was freeing British businesses to give them the headroom to maximise their productivity and contribution to the economy.”

That was “even more desperately needed now on the long road to recovery from the pandemic”, she added.

“Yet the only detectable impact so far is increased costs, paperwork and border delays,” Dame Meg said.

The MPs’ report also raised concerns about “potential for disruption at the border” as passenger traffic between Britain and Europe recovers later this year towards pre-pandemic levels – especially at ports such as Dover where EU officials carry out checks on the UK side.

Meanwhile “much remains to be done” as the government phases in import controls, already introduced on the European side, to ensure that continental traders and hauliers are ready, the committee said.

The report added that a plan to deliver, by 2025, the “most effective border in the world” looked “optimistic, given where things stand today” and the committee was not convinced by it.

It noted, for example, that HMRC needs to move all users of its existing customs system to its new Customs Declaration Service, but that by October 2021 only 42 out of 5,000 had done so.

A further concern raised by the MPs was that arrangements for goods arriving from the EU were “untested and could be exploited”.

One risk related to the delay in building infrastructure at Dover, which will not be ready until 2023.

Until then, lorries carrying goods selected for physical checks will have to travel 60 miles to Ebbsfleet, posing a risk that their cargoes could be offloaded on the way.

“HMRC agreed it would be ideal to have the infrastructure at the port itself and goods controlled at the port but said that it was not possible,” the report said.

“It told us it was looking at what surveillance it would need to manage those risks.”

The report comes two days before the Office for National Statistics publishes trade figures for December and 2021 as a whole – the first such annual data since the end of the transition period.