The government has been warned it is falling dangerously behind in its plans to build a British battery industry, with manufacturing capacity forecast to be barely half the needed level by the end of the decade, according to internal documents seen by Sky News.

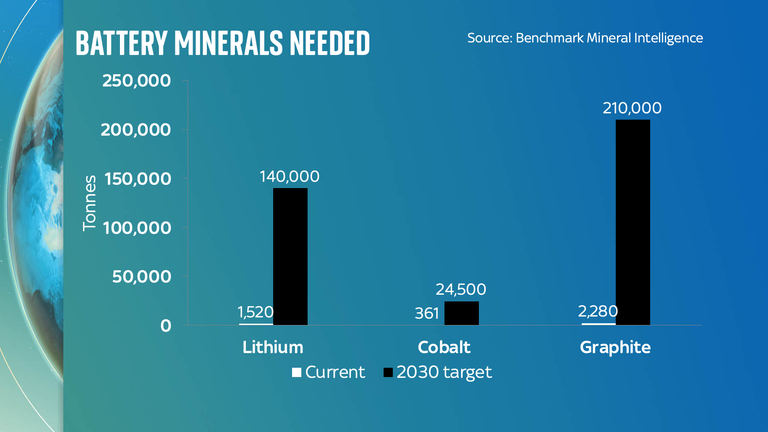

The dossier of figures submitted to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) shows that the UK will have to increase the amount of lithium, cobalt and graphite – critical ingredients in battery production – by staggering amounts, as much as 90 times the current level, to have any hope of supplying that industry.

The data, produced by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence – one of the world’s leading authorities on the battery industry and a member of the BEIS Critical Minerals Expert Committee – will raise questions about whether Britain’s car industry can be maintained at its current levels, as batteries replace engines as the single most valuable component of a motor vehicle.

With hundreds of thousands of jobs dependent on the transition, they raise deep questions about Britain’s economic trajectory in the coming years.

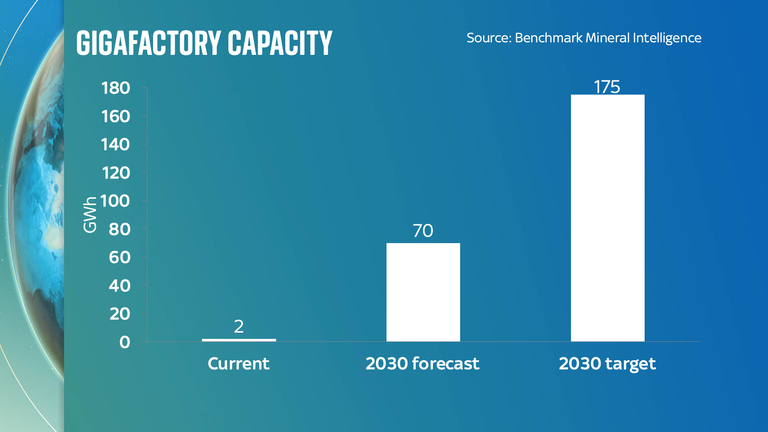

At the heart of them is a projection showing that by 2030, the year the government plans to ban the sale of internal combustion engine cars, it will not have enough gigafactories – large-scale battery plants – to sustain car production at current levels.

The Benchmark data projects the UK is likely to have just short of 70 gigawatt-hours of battery production, but that it should be targeting 175 GWh if it is to retain car production.

It is the equivalent of four of Tesla’s gigafactories – themselves among the biggest factories in the world.

The news comes only weeks after the government committed £100m of taxpayer money into a gigafactory proposal, Britishvolt, which will build a plant in the North East of England.

Nissan’s battery maker, Envision AESC, has also pledged to pump extra cash into its Sunderland plant where cells for the Leaf EV are produced.

However, even if these two projects produce at maximum capacity, the UK will still have less than half the battery production it needs by 2030.

Government insiders have told Sky News that they hope for perhaps one or two more gigafactory announcements in the coming months, revealing that they have been in discussions with a host of manufacturers, including Rivian, Polestar and Canoo, about future plants.

They have also had a “number of detailed conversations” with Tesla about it building a secondary European manufacturing hub, following its Gigafactory in Berlin.

Questions also remain about Jaguar Land Rover’s plans.

However, the numbers submitted to the government, which is actively pondering its strategy on critical minerals, also underlines the scale of physical materials needed for these factories.

It projects that the UK’s demand for lithium – the pivotal material in all mainstream rechargeable batteries – would rise from 1,500 tonnes this year to around 60,000 by 2030 on the basis of current gigafactory plans, and to 140,000 tonnes if the UK aims to increase its battery manufacturing in line with Benchmark’s recommended target.

There are similar increases projected in the need for graphite, nickel and manganese and a large if slightly less exponential increase in demand for cobalt (since producers are gradually reducing their need for the controversial metal, mined primarily in the Democratic Republic of Congo).

All told, the increase in the necessary supply of these critical metals will represent one of the biggest challenges for UK industry in the coming years.

In much the same way as the UK is affected by international demand for natural gas at present, it is likely to become locked in a similar race for the natural resources needed for battery production.

And while a certain chunk of UK lithium could be sourced from domestic mines, they remain at pilot stage, and might, depending on battery production, only provide around a half of UK needs.

More urgently, the Benchmark dossier warns that the UK’s biggest vulnerability is that while plenty of exploratory work has been done to exploit any available lithium and to finance the construction of new gigafactories, there remains a gaping void at the heart of the strategy.

The UK has no producers of either cathode active materials or anode materials – the intermediate step where the raw materials mined from the ground are turned into pristine chemicals which then get sent to gigafactories.

Johnson Matthey had been working on a cathode project, but abruptly pulled out late last year.

At present the global battery industry is dominated by Asian production in Japan, China and South Korea, but both the US and Europe have declared that they intend to build their own domestic supply chains.

With countries around the world having pledged to shift their car markets from petroleum towards battery power, this promises to be one of the biggest adjustments in modern industrial history, with many winners and losers.

The Benchmark data suggests that the UK’s plans may fall short of the ambitions being mapped out elsewhere.

A BEIS spokesperson said: “The UK continues to be one of the best locations in the world for auto manufacturing, with a major government investment programme of up to £1bn to electrify our supply chain and help meet future demand for batteries and their raw materials.

“As a result, we have already seen major investments in battery production from Britishvolt and Envision AESC which will create thousands of jobs across the country.

“We will also publish a strategy this year outlining how we will ensure the UK has a resilient, long term supply chain for critical minerals.”