A summit of NATO leaders in Brussels was meant as a show of unity against Russian President Vladimir Putin and of unwavering support for Ukraine.

But the 30-member alliance is performing a hugely difficult balancing act in an evolving response to Russia‘s war with its neighbour.

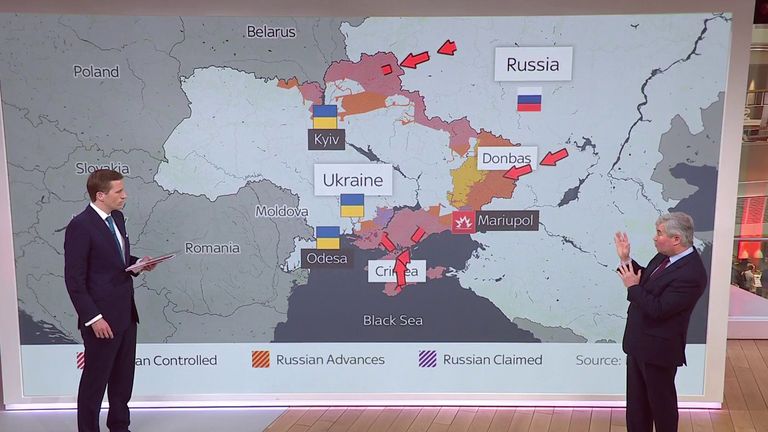

Allies needed to help the Ukrainian armed forces defend their territory, with individual member states providing various types of increasingly lethal weapons, but not assist so significantly that it’s viewed by Moscow as a direct intervention – something that could trigger World War Three.

Ukraine-Russia news live: NATO to provide four more battle groups in Eastern Europe

At the same time, there is much less regard about angering Russia when it comes to bolstering the number of troops, warships and jets on a higher state of readiness within the alliance’s own borders – something that previously restricted NATO’s willingness to strengthen its ability to defend against and deter Russian aggression.

When it comes to Ukraine, which is not a NATO member, there remains a gap between a new request for support from Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the country’s wartime president, and what countries are willing to give.

The space did seem to be shrinking as the Ukrainian leader, who addressed allies at the morning summit remotely by video-link, appeared to adjust his requirements.

Change in no-fly zone demand

He no longer asked for a no-fly zone – something that had been a mantra for the Ukrainian government since the start of the invasion, but which countries like the US and the UK have rejected as unworkable.

This is because it would require NATO jets to shoot Russian war planes and missiles out of the sky and destroy Russian air defence systems to defend Ukraine’s air space.

That kind of action could quickly lead to a full-scale war in Europe with much greater death, destruction and human suffering.

Instead, President Zelenskyy asked for more potent fighting equipment than the (albeit vital) anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles he is already receiving, making a pitch for 1% of all NATO warplanes and tanks.

But this too could potentially breach an invisible threshold of western assistance, shifting from allies gifting more arguably defensive weapons to more offensive ones.

Jens Stoltenberg, the NATO secretary general, whose term in office was extended for another year because of the war – a move that prompted a round of applause from the leaders – explained the dilemma when asked about the Ukrainian request during a news conference after the summit.

“NATO allies provide significant support to Ukraine and we provide also lethal weapons, advanced systems and also systems that help them to shoot down planes and attack battle tanks with anti-tank weapons and many other types of systems including drones,” he said.

“At the same time we have a responsibility to prevent this conflict from becoming a full-fledged war in Europe, involving not just Ukraine and Russia but NATO allies and Russia. That would be more dangerous and more devastating and I think we have to be honest about that and that is exactly what we were being in our meeting today.”

Another balancing act is also being carried out by NATO when it comes to spelling out how allies would respond should President Putin launch a chemical or biological weapons attack in Ukraine.

If the West makes such action a red line requiring a direct NATO military intervention, then once again the consequences risk blowing up into the Third World War.

Finally – though no longer as pronounced – there is a balance to be struck for the alliance as it strengthens its own ability to deter Russian aggression.

Every NATO move can be twisted by Moscow

NATO plans to deploy even more soldiers, warships and jets at high readiness across the alliance but every move it makes can be twisted by the Kremlin to accuse allies of being the aggressors and to justify greater Russian hostilities against them.

This equation is becoming less difficult to manage, however, than it was back in 2014 when the alliance first had to reset significantly its defence and deterrence posture in response to Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine, when Moscow annexed Crimea.

At that time, the desire was to strengthen the alliance’s eastern flank by creating battlegroups in the Baltic states and Poland.

But there was a nervousness about going too far and triggering an escalatory response from Russia.

Previous NATO posture clearly failed

Yet the posture that was agreed upon back then has clearly failed given President Putin felt he could, however mistakenly, get away with launching an all-out war against Ukraine eight years later.

It means the alliance is no longer allowing itself to be limited in its actions by an agreement struck between NATO and Russia back in 1997 that set out fundamental principles limiting the deployment of NATO forces on the territory of member states.

As a result, NATO has been exponentially faster in expanding the original battlegroups and now setting up four new ones in Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Slovakia – something confirmed at the summit.

They have also activated an emergency NATO Response Force for the first time and put swathes of allied military personnel on a higher state of readiness.

Further longer-term decisions on force sizes and postures are set to be taken at another leaders’ summit in June.

Pledges to bolster defence spending are also being accelerated – a sign that NATO has found a renewed sense of purpose and that all allies are starting to relearn the reality that their security and values cannot be guaranteed without credible defences.